Spaceship Operator

You write a class. It has a bunch of member data. At some point, you realise that you need to be able to compare objects of this type. You sigh and resign yourself to writing six operator overloads for every type of comparison you need to make. Afterwards your fingers ache and your previously clean code is lost in a sea of functions which do essentially the same thing. If this sounds familiar, then C++20’s spaceship operator is for you. This post will look at how the spaceship operator allows you to describe the strength of relations, write your own overloads, have them be automatically generated, and how correct, efficient two-way comparisons are automatically rewritten to use them.

Relation strength

The spaceship operator looks like <=> and its official C++ name is the “three-way comparison operator”. It is so-called, because it is used by comparing two objects, then comparing that result to 0, like so:

(a <=> b) < 0 //true if a < b

(a <=> b) > 0 //true if a > b

(a <=> b) == 0 //true if a is equal/equivalent to b

One might think that <=> will simply return -1, 0, or 1, similar to strcmp. This being C++, the reality is a fair bit more complex, but it’s also substantially more powerful.

Not all equality relations were created equal. C++’s spaceship operator doesn’t just let you express orderings and equality between objects, but also the characteristics of those relations. Let’s look at two examples.

Example 1: Ordering rectangles

We have a rectangle class and want to define comparison operators for it based on its size. But what does it mean for one rectangle to be smaller than another? Clearly if one rectangle is 1cm by 1cm, it is smaller than one which is 10cm by 10cm. But what about one rectangle which is 1cm by 5cm and another which is 5cm by 1cm? These are clearly not equal, but they’re also not less than or greater than each other. But speaking practically, having all of <, <=, ==, >, and >= return false for this case is not particularly useful, and it breaks some common assumptions at these operators, such as (a == b || a < b || a > b) == true. Instead, we can say that == in this case models equivalence rather than true equality. This is known as a weak ordering.

Example 2: Ordering squares

Similar to above, we have a square type which we want to define comparison operators for with respect to size. In this case, we don’t have the issue of two objects being equivalent, but not equal: if two squares have the same area, then they are equal. This means that == models equality rather than equivalence. This is known as a strong ordering.

Describing relations

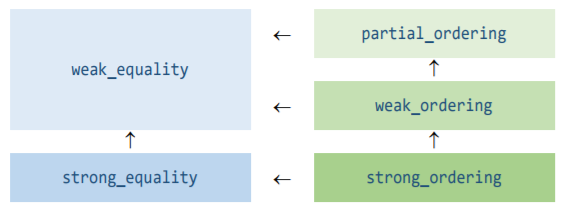

Three-way comparisons allow you express the strength of your relation, and whether it allows just equality or also ordering. This is achieved through the return type of operator<=>. Five types are provided, and stronger relations can implicitly convert to weaker ones, like so:

Strong and weak orderings are as described in the above examples. Strong and weak equality means that only == and != are valid. Partial ordering is weaker than weak_ordering in that it also allows unordered values, like NaN for floats.

These types have a number of uses. Firstly they indicate to users of the types what kind of relation is modelled by the comparisons, so that their behaviour is more clear. Secondly, algorithms could potentially have more efficient specializations for when the orderings are stronger, e.g. if two strongly-ordered objects are equal, calling a function on one of them will give the same result as the other, so it would only need to be carried out once. Finally, they can be used in defining language features, such as class type non-type template parameters, which require the type to have strong equality so that equal values always name the same template instantiation.

Writing your own three-way comparison

You can provide a three-way comparison operator for your type in the usual way, by writing an operator overload:

struct foo {

int i;

std::strong_ordering operator<=> (foo const& rhs) {

return i <=> rhs.i;

}

};

Note that whereas two-way comparisons should be non-member functions so that implicit conversions are done on both sides of the operator, this is not necessary for operator<=>; we can make it a member and it’ll do the right thing.

Sometimes you may find that you want to do <=> on types which don’t have an operator<=> defined. The compiler won’t try to work out a definition for <=> based on the other operators, but you can use std::compare_3way instead, which will fall back on two-way comparisons if there is no three-way version available. For example, we could write a three-way comparison operator for a pair type like so:

template<class T, class U>

struct pair {

T t;

U u;

auto operator<=> (pair const& rhs) const

-> std::common_comparison_category_t<

decltype(std::compare_3way(t, rhs.t)),

decltype(std::compare_3way(u, rhs.u)> {

if (auto cmp = std::compare_3way(t, rhs.t); cmp != 0) return cmp;

return std::compare3_way(u, rhs.u);

}

std::common_comparison_category_t there determines the weakest relation given a number of them. E.g. std::common_comparison_category_t<std::strong_ordering, std::partial_ordering> is std::partial_ordering.

If you found the previous example a bit too complex, you might be glad to know that C++20 will support automatic generation of comparison operators. All we need to do is =default our operator<=>:

auto operator<=>(x const&) = default;

Simple! This will carry out a lexicographic comparison for each base, then member of the type, in order of declaration.

Automatically-rewritten two-way comparisons

Although <=> is very powerful, most of the time we just want to know if some object is less than another, or equal to another. To facilitate this, two-way comparisons like < can be rewritten by the compiler to use <=> if a better match is not found.

The basic idea is that for some operator @, an expression a @ b can be rewritten as a <=> b @ 0. For example, a < b is rewritten as a <=> b < 0. These can even be rewritten as 0 @ b <=> a if that is a better match, which means we get symmetry for free.

In some cases, this can actually provide a performance benefit. Quite often comparison operators are implemented by writing == and <, then writing the other operators in terms of those rather than duplicating the code. This can lead to situations where we want to check <= and end up doing an expensive comparison twice. This automatic rewriting can avoid that cost, since it will only call the one operator<=> rather than both operator< and operator==.

Conclusion

The spaceship operator is a very welcome addition to C++. It gives us more expressiveness in how we define our relations, lets us write less code to define them (sometimes even just a defaulted declaration), and avoids some of the performance pitfalls of manually implementing some comparison operators in terms of others.

For more details, have a look at the cppreference articles for comparison operators and the compare header, and Herb Sutter’s standards proposal. For a good example on how to write a spaceship operator, see Barry Revzin’s post on implementing it for std::optional. For more information on the mathematics of ordering with a C++ slant, see Jonathan Müller’s blog post series on the mathematics behind comparison.

Let me know what you think of this article on twitter @TartanLlama or leave a comment below!