std::accumulate vs. std::reduce

std::accumulate has been a part of the standard library since C++98. It provides a way to fold a binary operation (such as addition) over an iterator range, resulting in a single value. std::reduce was added in C++17 and looks remarkably similar. This post will explain the difference between the two and when to use one or the other.

Let’s start by looking at their interfaces, beginning with std::accumulate.

template< class InputIt, class T >

T accumulate( InputIt first, InputIt last, T init );

template< class InputIt, class T, class BinaryOperation >

T accumulate( InputIt first, InputIt last, T init,

BinaryOperation op );

std::accumulate takes an iterator range and an initial value for the accumulation. You can optionally give it a binary operation to do the reduction, which will default to addition. It will call this operation on the initial value and the first element of the range, then on the result and the second element of the range, etc. Here are two equivalent calls:

auto sum1 = std::accumulate(begin(vec), end(vec), 0);

auto sum2 = std::accumulate(begin(vec), end(vec), 0, std::plus<>{});

std::reduce has a fair few more overloads to get your head round, but has a very similar interface once you understand them:

template<class InputIt>

typename std::iterator_traits<InputIt>::value_type reduce(

InputIt first, InputIt last);

template<class ExecutionPolicy, class ForwardIt>

typename std::iterator_traits<ForwardIt>::value_type reduce(

ExecutionPolicy&& policy,

ForwardIt first, ForwardIt last);

template<class InputIt, class T>

T reduce(InputIt first, InputIt last, T init);

template<class ExecutionPolicy, class ForwardIt, class T>

T reduce(ExecutionPolicy&& policy,

ForwardIt first, ForwardIt last, T init);

template<class InputIt, class T, class BinaryOp>

T reduce(InputIt first, InputIt last, T init, BinaryOp binary_op);

template<class ExecutionPolicy, class ForwardIt, class T, class BinaryOp>

T reduce(ExecutionPolicy&& policy,

ForwardIt first, ForwardIt last, T init, BinaryOp binary_op);

The differences here are:

- You can optionally provide an execution policy.

reduceis overloaded for input iterators and forward iterators.- Supplying the initial element is optional (default construction of the value type is used by default).

I’ll talk about these points in turn.

Execution policies

Execution policies are a C++17 feature which allows programmers to ask for algorithms to be parallelised. There are three execution policies in C++17:

std::execution::seq– do not parallelisestd::execution::par– parallelisestd::execution::par_unseq– parallelise and vectorise (requires that the operation can be interleaved, so no acquiring mutexes and such)

The idea behind execution policies is that you can change a serial algorithm to a parallel algorithm simply by passing an additional argument to the function:

auto sum1 = std::reduce(begin(vec), end(vec)); //sequential

auto sum2 = std::reduce(std::execution::seq, begin(vec), end(vec)); //sequential

auto sum3 = std::reduce(std::execution::par, begin(vec), end(vec)); //parallel

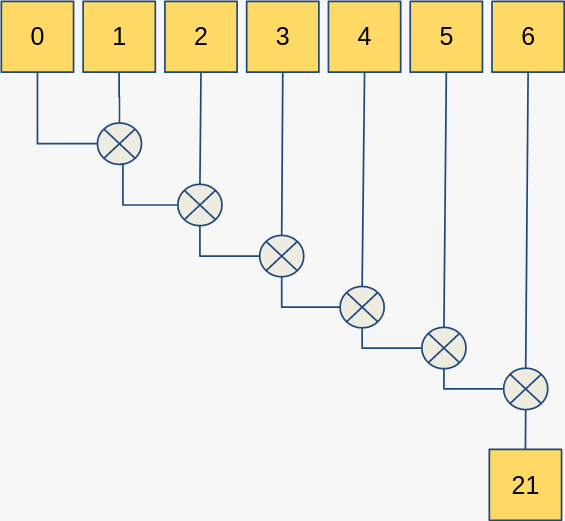

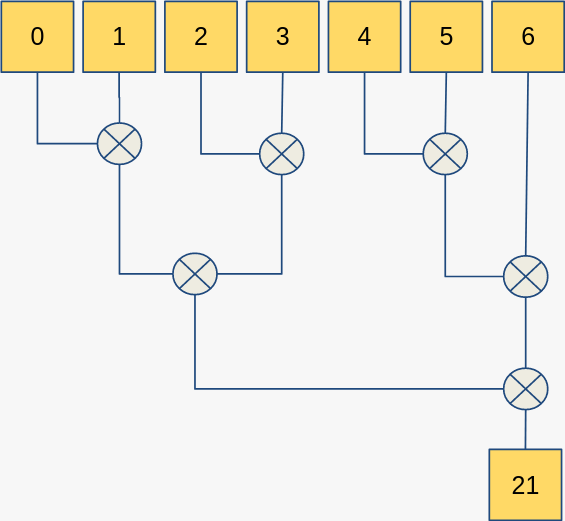

Allowing parallelisation is the main reason for the addition of std::reduce. Let’s look at an example where we want to sum up all the elements in an array. With std::accumulate it looks like this:

Note that each step of the computation relies on the previous computation, i.e. this algorithm will execute serially and we make no use of hardware parallel processing capabilities. If we use std::reduce with the std::execution::par policy then it could look like this:

This is a trivial amount of data for processing in parallel, but the benefit gained when the data size is scaled up should be clear: some of the operations can be executed independently of others, so they can be done in parallel.

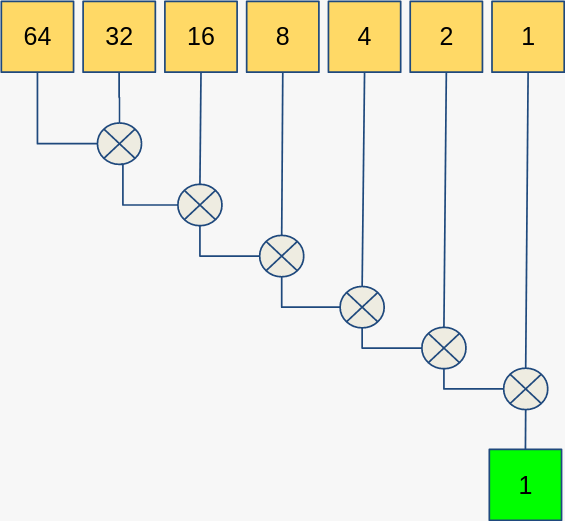

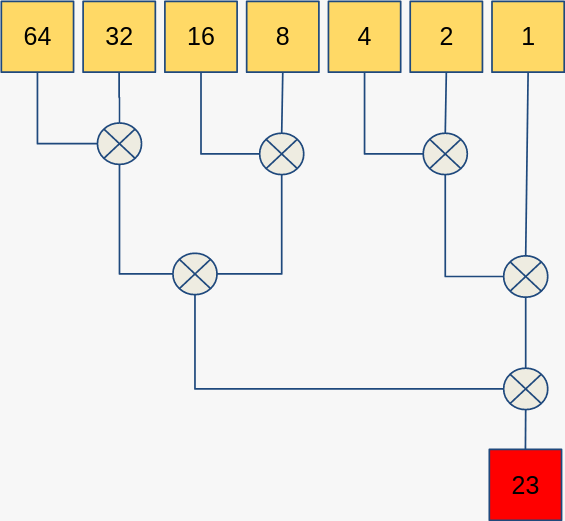

A common question is: why do we need an entirely new algorithm for this? Why can’t we just overload std::accumulate? For an example of why we can’t do this, let’s use std::minus<> instead of std::plus<> as our reduction operation. With std::accumulate we get this:

However, if we try to use std::reduce, we could get something like:

Uh oh. We just broke our code.

We got the wrong answer because of the mathematical properties of subtraction. You can’t arbitrarily reorder the operands, or compute the operations out of order when doing subtraction. This is formalised in the properties of commutativity and associativity.

A binary operation ∗ on a set S is associative if the following equation holds for all x, y, and z in S:

(x ∗ y) ∗ z = x ∗ (y ∗ z)

An operation is commutative if:

x ∗ y = y ∗ x

Associativity lets the algorithm compute reduction steps on arbitrary adjacent pairs of elements. Commutativity allows carrying out the operation on intermediate results in whatever order they are produced in, rather than having to preserve the original ordering. Some people (e.g. here and here) find that commutativity is too strong a requirement on std::reduce, because it denies use of common fold operations like string concatenation, which is associative but not commutative. I agree that it’s a shame we don’t have a step between std::accumulate and std::reduce which only requires associativity, but maybe in the future!

We can understand how associativity and commutativity affect our algorithm as much as we want, but there’s no way for the compiler to reliably check this. As such, we’re stuck with having std::reduce as a separate algorithm. In concepts speak, these are called axioms1: requirements imposed on semantics which cannot generally be statically verified.

Input vs. Forward Iterators

The forward iterator overloads allow the implementation to chunk up the data and dispatch these subranges to different threads. The idea is that input iterators are single-pass, whereas forward iterators can be iterated through multiple times. An algorithm couldn’t chunk up data indexed by input iterators because by the time it had gone through the range to work out the sub-range boundaries, the iterators will have been invalidated and can’t be passed on.

For more information on iterator types and parallel algorithms, see p0467r2.

Optional Initial Element

std::reduce lets you not bother passing an initial element, in which case it will default-construct one using typename std::iterator_traits<InputIt>::value_type{}. I think this was a mistake. A default-constructed value is not always the identity element (such as in multiplication), and it’s very easy to for a programmer to miss out the initial element. The code will still compile, it will just give the wrong answer. I suspect that this choice will result in some hard-to-find bugs when this interface comes into heavier use.

Finishing Up

That covers the differences between std::reduce and std::accumulate. My three point guide to std::reduce is:

- Use

std::reducewhen you want your accumulation to run in parallel - Ensure that the operation you want to use is both associative and commutative

- Remember that the default initial value is produced by default construction, and that this may not be correct for your operation

Now you know how and when to use std::reduce over std::accumulate. More generally, the differences show some of the technical aspects you need to consider when parallelising any kind of algorithm. Keep in mind how your operations act with respect to common mathematical properties and you might save yourself some debugging down the line.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Christopher Di Bella for reviewing this post and linking me to p0467r2. Thanks to Ben Steffan, Ben Deane, and TemplateRex for discussion about commutativity.

-

For more about axioms and algorithms, see this post by Christopher Di Bella. ↩

Let me know what you think of this article on twitter @TartanLlama or leave a comment below!